I’M NOT GOVERNED BY MY FLESH, Lagos Nigeria

Between Heaven and Flesh is the The Ancestral Architecture of Becoming

There are moments in art when the spiritual and the material cease to exist as opposites and instead become two dialects of the same language. In this body of work, that language is spoken through women crowned with horns, through the gaze of a cow resting beside them, through the quiet rumble of pigment pressed into a rough, earthen canvas. Lulama Wolf has used this medium to inhabit the threshold between heaven and earth, where the divine ceases to be distant and instead takes shape in flesh, ritual, and ancestral memory.

Drawing from the passage in Matthew 6:10,“Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven”, the work meditates on the permeability between spiritual aspiration and earthly existence. Heaven, here, is not imagined as a distant paradise, but as a living principle, a vibration embedded in the soil, the body, the blood. Because it is so fluid, this work interrogates far more than heaven and earth as places of refuge. It symbolises something more profound: the embodiment of the sacred within the female form, and the ancestral continuum that sustains it.

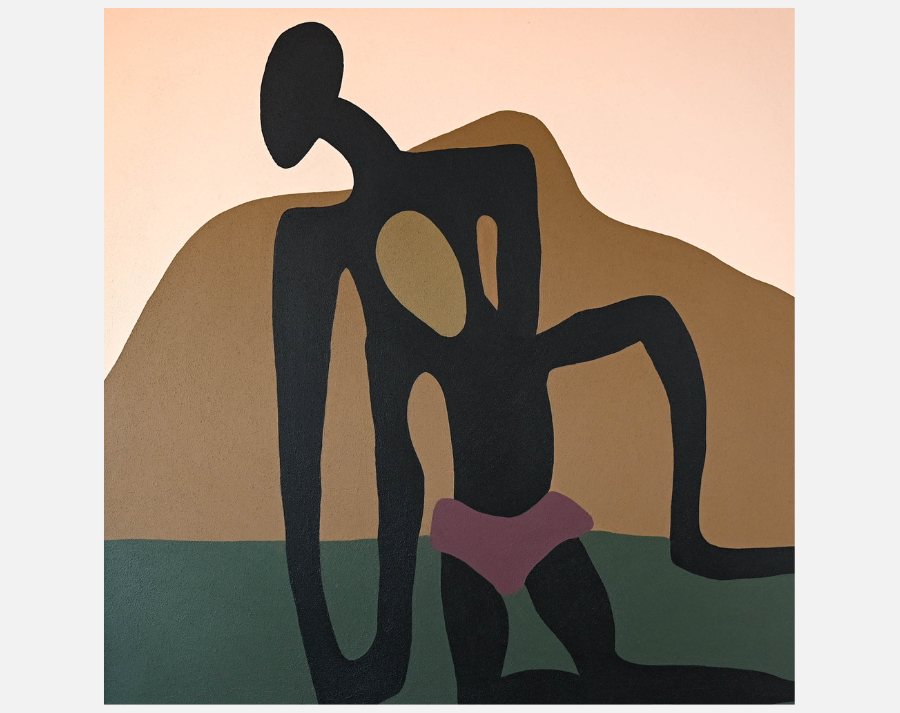

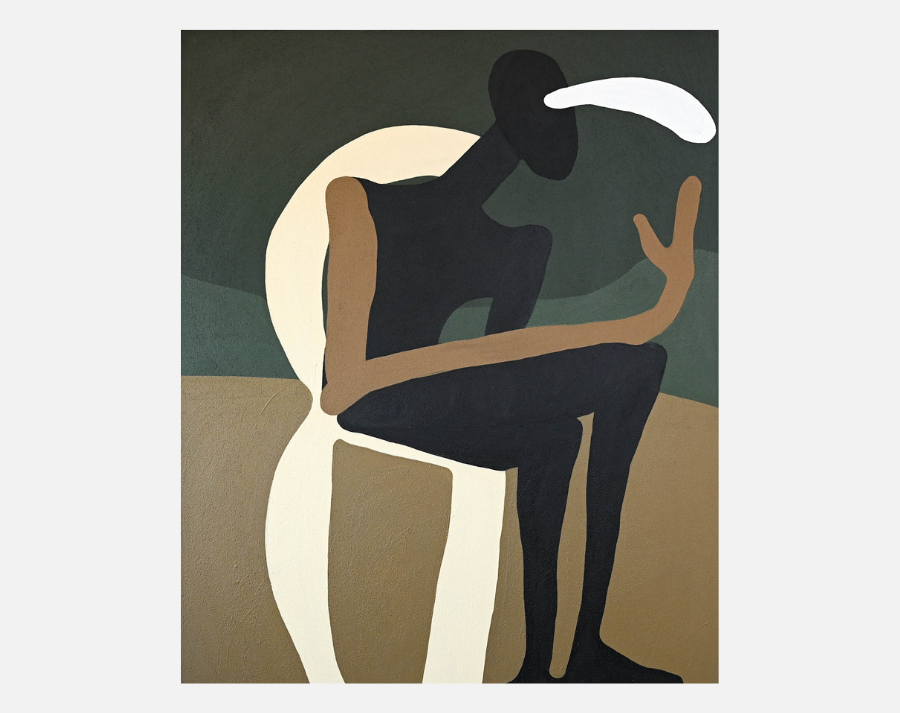

... The subjects in this body of work are delicate and restful, yet undeniably powerful. They carry the duality of fragility and endurance which is the paradox of being both vessel and source. These figures are not representations in the Western sense, but embodiments; they carry within them the texture of myth and memory.

Nigerian scholar Nkiru Nzegwu writes that African visual traditions “do not conceive of beauty as surface, but as a moral and cosmological order made visible through the human form.” In her analysis of Igbo aesthetics, the female figure is an archive of communal values which include beauty, fertility, continuity and balance. The women in these paintings exist in that same tradition: not as objects of gaze, but as mediators between seen and unseen worlds. Horns emerge from their heads, not as ornaments but as ancestral extensions of will. In Igbo philosophy, the ikenga which is a human figure with horns embodies - power, persistence, and divine favour. In these paintings, horns crown the feminine not to masculinise it, but to amplify it; they become conduits for intuition and spiritual strength. The woman, as caretaker and mother, is transfigured into a cosmic matriarch, earthly yet celestial, grounded yet ascendant.

Threaded through these works, is a conversation between animal and feminine. It is a sacred dialogue that blurs the boundaries between offering and offered, between nurturer and sacrifice. Across much of the African continent, animals are not symbols of domination but partners in creation and transition. This understanding infuses the imagery of cows, horns and hybrid females in animal forms within this series. The cow, a central motif, recalls its role in rites of passage through its blood, sealing marriages, births, and reparations. It is both sustenance and sacrifice, mediator and message. When paired with women, it speaks of continuity, care, and ancestral covenant.

To take a woman from her family, cattle must be given; to welcome a child into lineage, blood must be spilled. In those moments, as the artist notes,“the human and the animal become one.” This is not violence, but communion. The shared offering through which the living negotiate with the divine. If the first gesture of the work is invocation, the second is reconciliation. The paintings become acts of reparation - between body and spirit, heaven and home. Wolf reminds us “Home, will always be heaven.” Yet heaven here is not an escape, but a return: a homecoming through surrender, forgiveness, and ancestral recognition.

The mythology that pulses through these works is not drawn from European classicism but from African cosmologies, where gods are intimate, and creation is continuous. The horned woman evokes deities such as Ani, the Igbo earth goddess of morality and fertility, or the Akan Akuaba, the spirit of beauty and motherhood. These figures remind us that the divine feminine is not fragile — it is foundational. Scholar Naminata Diabate writes of “embodied agency” in African feminist aesthetics — the body as a site of protest, prayer, and transformation. Here, embodiment becomes theology. When the artist declares,“My flesh bows to my spirit,” she articulates a surrender that is not submission but alignment: the reconciliation of the physical and spiritual orders, of heaven and earth.

The tactile surface of the canvas is integral to the work’s meaning. The roughness of the linen, the density of pigment, the subdued glow of soft pinks, whites and burgundy. These choices are not decorative, but devotional. They recall the granularity of soil, the resilience of skin, the residue of ritual. African art has long privileged materiality as a form of metaphysical truth. Congolese philosopher and artist Muntu Masudi once observed that “the African artist does not depict spirit; she summons it.” In this sense, the thick texture of the canvas becomes invocation: a calling forth of the unseen into the seen. Pigments remain subdued, whispering rather than shouting. The neutrals and whites carry the tenderness of flesh, of dawn light, of divine breath; burgundy grounds the work in the blood of sacrifice and lineage. The result is an aesthetic that is simultaneously gentle and forceful, ephemeral yet deeply embodied — a visual articulation of the sacred as lived experience.

The guiding theological question “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” is not merely recited here; it is performed. The paintings enact this petition by dissolving the distinction between heaven and earth. Heaven is no longer a destination but a resonance, a frequency that hums through the gestures of care, the rituals of offering, the labour of creation. The figures, though bearing horns, appear restful, even fragile. This compositional quietness amplifies their spiritual weight. They do not struggle toward divinity; they receive it. They model what John Mbiti famously described as “African religiosity without separation” where “God is not beyond reach, but within the rhythm of daily life.” The divine is here, in the feminine, in the animal, in the texture of paint.

The recurring motif of offering, whether in cattle or pigment, recalls pan-African ritual logics of exchange: one life honouring another, one body bridging two realms. In the southern regions, the Zulu idiom “ukuhlabela amadlozi” to sacrifice to the ancestors describes the act of feeding the spiritual lineage. In Ghana, the Akan concept of sunsum situates the soul as an inheritable energy connecting individuals to their forebears. These cosmologies affirm that the act of offering is not a payment, but a form of kinship.

The paintings are both altar and archive, both prayer and prophecy. They remind us that heaven and earth are not opposing poles, but mirrors, each reflecting the other’s infinite depth. It is the gaze of a woman preparing to return home, the shimmer of white invoking spirit and dawn. In this light, the paintings become visual offerings with each brushstroke an invocation, each textured surface a libation.

Wolf explores the relationship between both prophet and participant, mediating between the tangible and the transcendent. Ultimately, it tells us that the divine is not waiting in some distant paradise — it is already here, pulsing in the rhythm of our blood, rising through the earth beneath our feet. Heaven is not elsewhere. It is now. It is us.

Written and Curated by Anelisa Mangcu