The Essence of Being

In this presentation, the artists contemplate personal identity and human connectivity. Distinct, familial muses evoke nuanced conversations surrounding belonging and absolutes. From Nobakada's reflections on feminine beauty and aesthetics; to Onosowobo’s questions surrounding cultural dissonance. Alongside, Maluleke’s meditations on spirituality through aquatic imagery and treasured momentos. Each artist considers the fluidity between what is given and what is chosen.

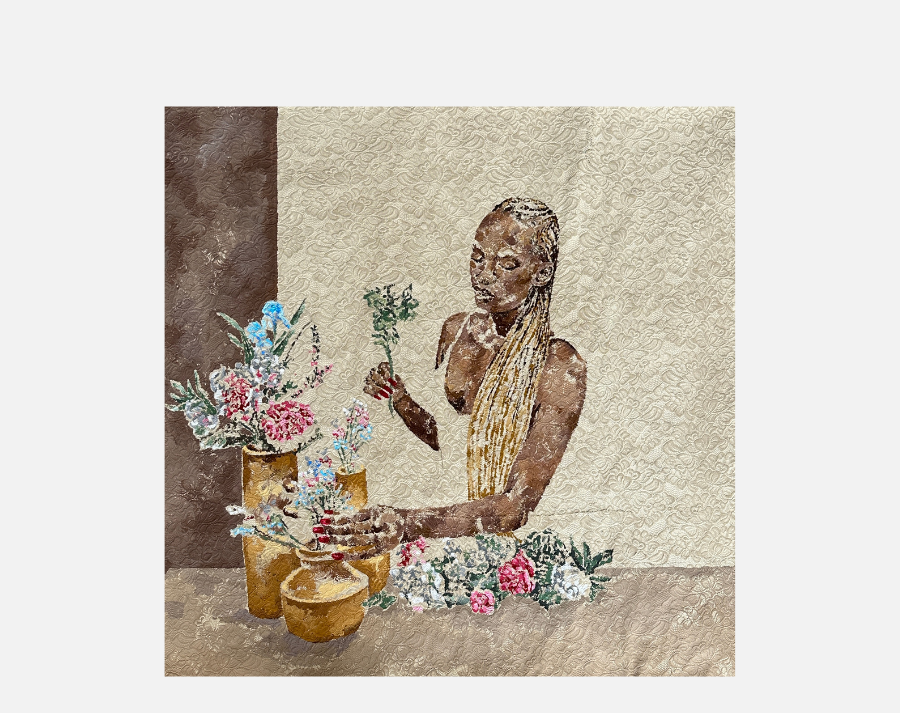

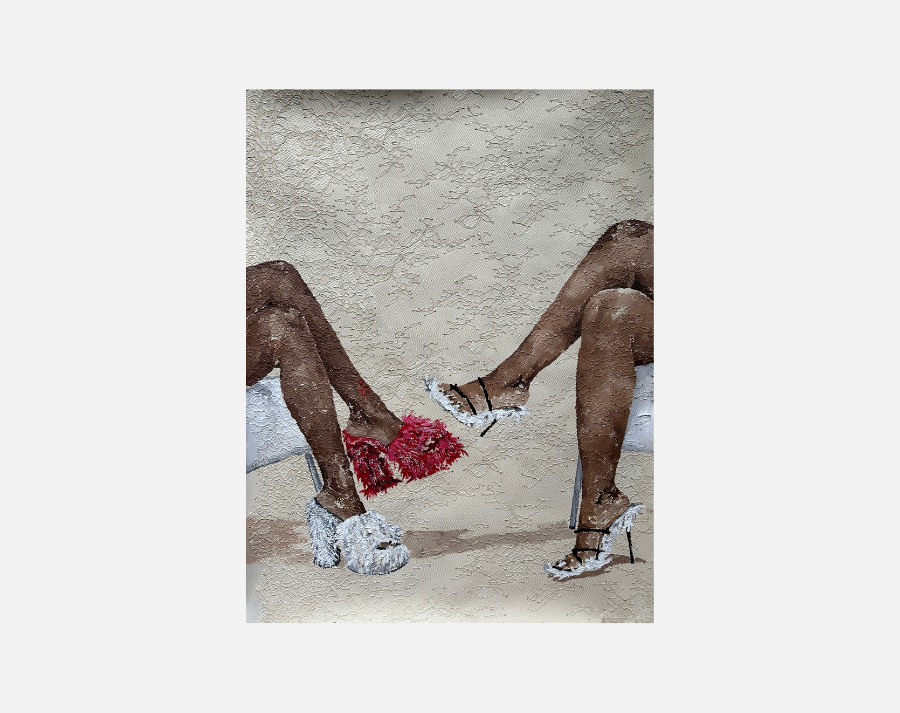

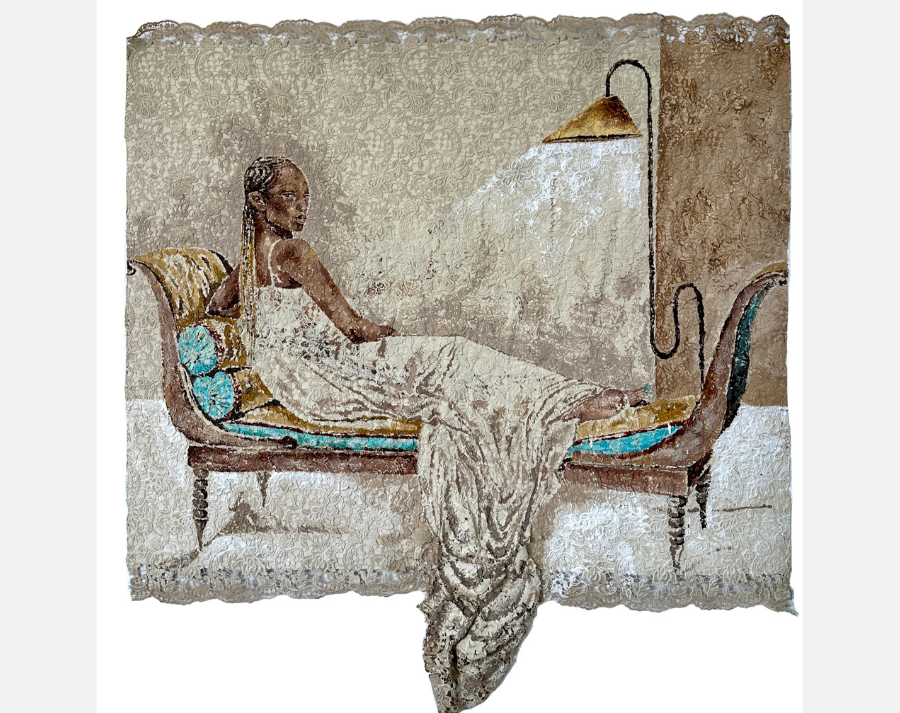

Through these works, Buqaqawuli Nobakada, presents a critical, utopian vision and protest. Her delicate yet firm interaction of acrylic with lace, communicates softness and precision. Using her cousin Zenande, she aims to reimagine and platform Black hyper-femininty. In her work, Portrait of Madame Zenande, she drew inspiration from Jacques-Louis David's Portrait of Madame Récamier (1800). She inserts Black feminine aesthetics into the Western art historical canon, a structure from which they have been systematically erased. Nobakada’s material geography celebrates contemporary Black women’s opulence and luxury.

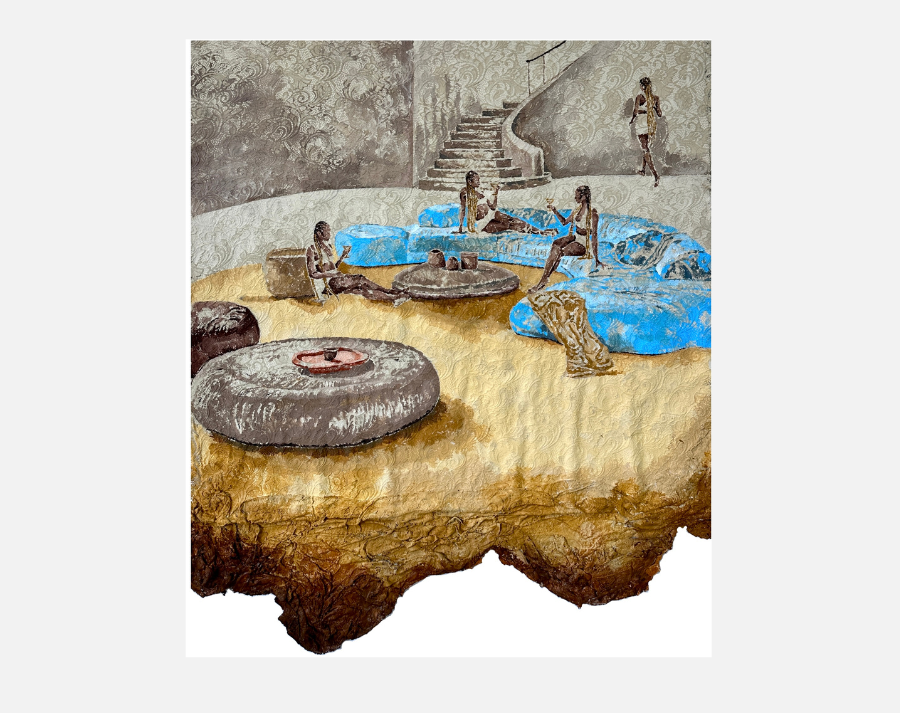

... The ordinary and nostalgia are centerfold in Damilola Onosowobo’s practice. Her work discusses everyday Nigerianness using motifs of memory and time. This new body of work presents a painterly dreamscape that poses questions rather than answers. As a Nigerian Yoruba woman, who toys with colonial legacies and globalization- she asks herself, “What is ours?”. In Laying Still Not Laying Still, she orientates herself by engaging with her immediate body as muse. Her confusions are un-ready and loosened. Terence Maluleke uses aquatic bodies to create a familial refrain. His lyrical use of geometric architecture builds a subtle yet bold world. His presentation is an homage to a childhood gift given to him by the late Jackson Hlungwani. This exquisite wooden fish sculpture is reinterpreted in each painting. Suspended and held with human bodies within fuller, watery compositions. The sea serves as a vessel through which contemplations concerning religiosity, spirituality and self are welcome.

These artists expound upon notions of familiarity and personhood, self-determining themselves through curiosity.

Thamani

Black feminism is distinctive in its commitment to love as a political practice.” - Nash, J: Love in the Time of Death

Nobakada's artistry pays homage to Black women’s contemporary craftsmanship and aesthetic performances. With her work, she is creating a particular Black feminist, afro-futurist spatiality. Her material geographies indulge in Black opulence and luxury. Through, using mediums such as acrylic on hand-prepared laced paper and, appendages made from custom clay or gold jewellery.

She seeks to share delicate, gentle indulgences with others. Hoping to craft a dimension for Black female protagonists who reside in exaggerated, abundant domesticity. Nobakada’s work reflects the regal performances of femininity and beauty she finds herself surrounded by. As she navigates tensions between traditional and modern expressions of postcolonial beauty. With, the growing socioeconomic autonomy of women in mind.

Nobakada's oeuvre diverges from conventional modes of understanding, reasserting an aesthetic that she earnestly regards as a form of elevated art. Her work is a communal manifestation that serves as a love letter to herself and other Black women and girls who come from townships and rural areas.

This body of work presents a nuanced critique and utopian vision; that liberates Black women from narrowed depictions in popular culture.

Nobakada’s cousin, Zenande, serves as her muse.

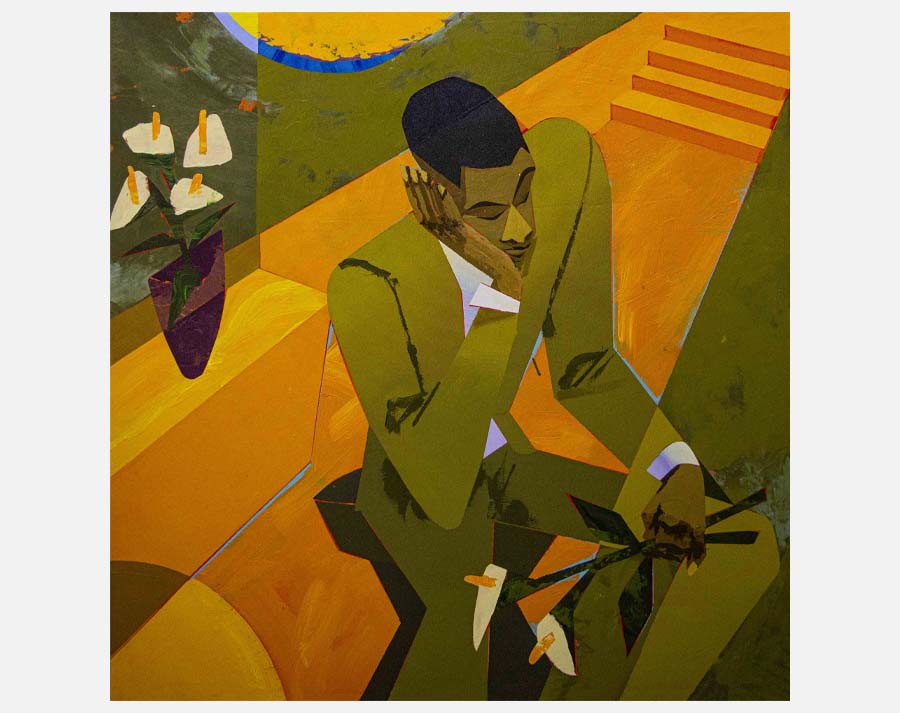

Dami

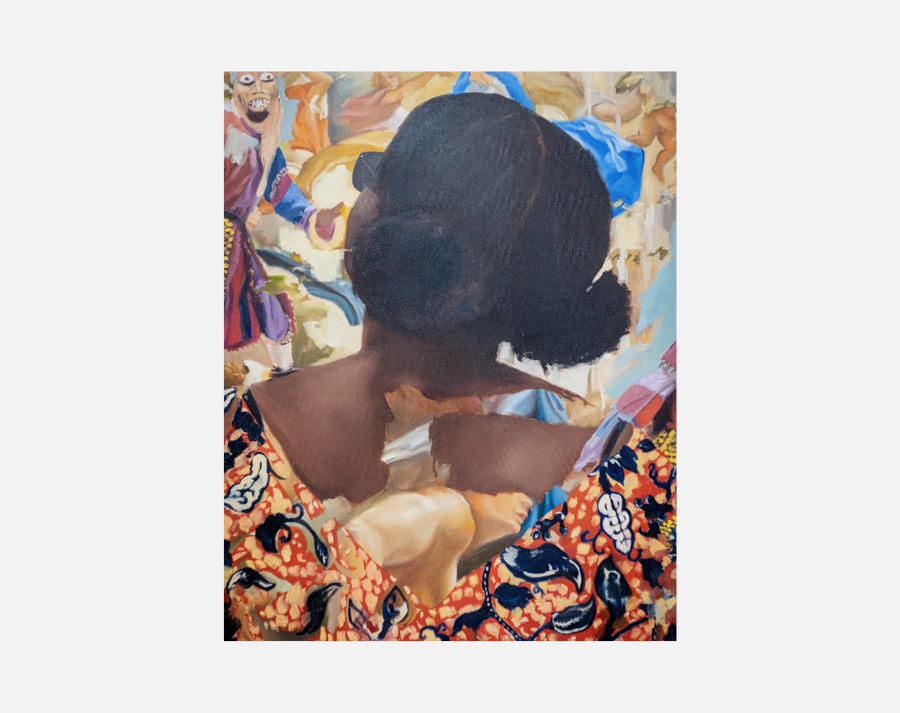

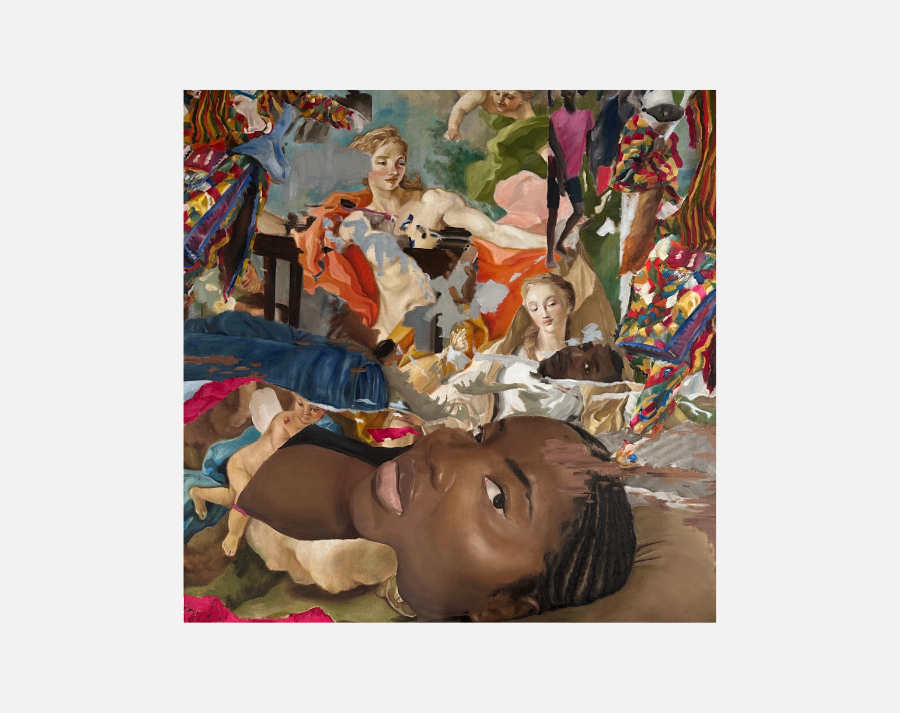

Nostalgia, familiarity, home, simple times, everyday Nigerianness- these are themes that Onosowobo typically explores within her artistic canon. Each year serves as a layered moment that is eventually displayed on canvas through oil. Her current focus is curiosity, she allows herself to be contemplative in her works. Questions fascinate her much more than answers.

This current series of works, ponders her confusions and un-readied thoughts. She is contorting herself within various surroundings- playing with the stages of grief and combat that encapsulate the inward journey.

As a Nigerian Yoruba woman, Onosowobo investigates the loosened threads between herself and her wider culture. This self-described ‘gap’, exemplifies the impacts of Western colonialism. This fractured cultural history bodes questions surrounding possession and heritage. She asks herself, “What is ours?”. Global modernity clearly informs her personal assemblage of self.

Yet, the chaos of experiencing a nation that is partially dissociated from itself is somewhat disorientating. Onosowobo re-contextualise these complexities through her own lens.

“It’s kind of a progression of what my work has always been about. This time, it’s beyond reminiscing. It’s a cultural question that I can never answer.”

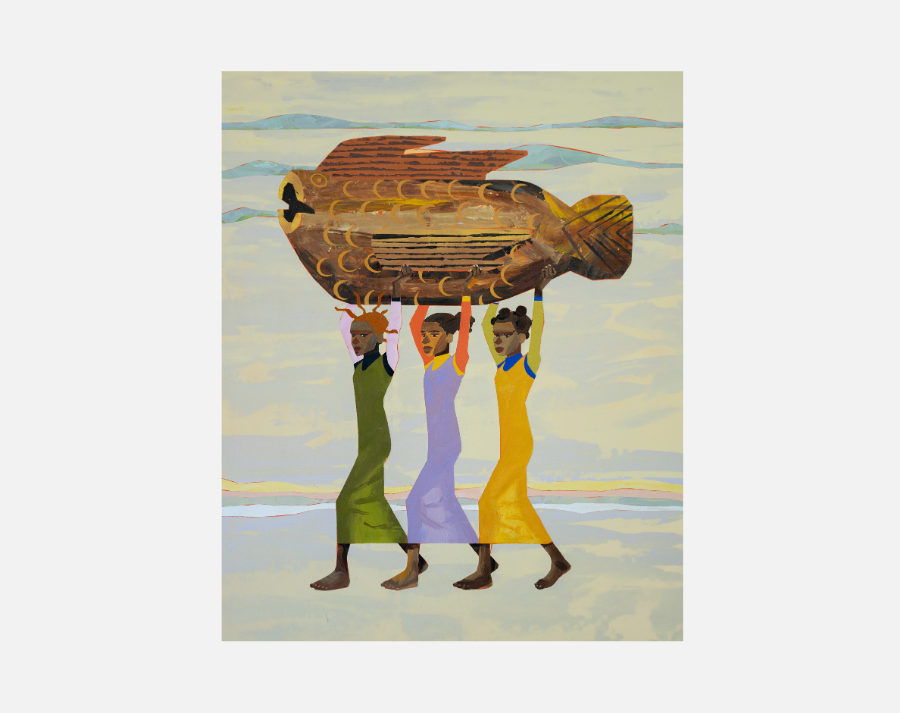

Terrence

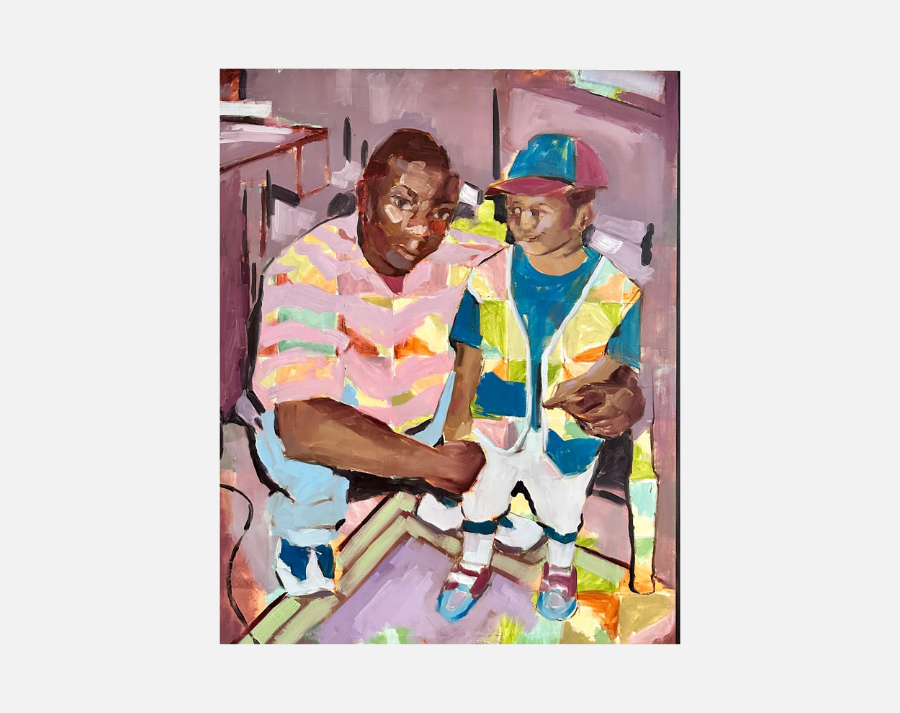

Maluleke is interested in the human form. His subtle, bodily figurations welcome us to retrieve what is below the surface.

Maluleke’s presentation is an homage to the late Jackson Hlungwani. A prolific sculptor whose practice used Tsonga-Shangaan wood carving, as a contemplation on spirituality and community. Much like Maluleke’s own practice, which is concerned with the interplay of self and system in spiritual and familial spaces.

In 2007, Hlungwani gifted Maluleke an exquisite wooden fish sculpture that is reinterpreted in each painting. The fuller, watery compositions are foregrounded in the dynamic, gestural fish. Either held, or suspended by the bodies that tenderise this allegory. Maluleke’s gift is now paid forward to the viewer, inviting them to speculate with him. Each canvas acts a waterbed that holds specific cultural-spiritual resonance within Tsonga culture.

Maluleke’s sea serves as a vessel through which contemplations concerning religiosity, spirituality and personhood are welcome. He uses aquatic bodies to create a familial refrain. His lyrical use of geometric architectures, builds a gentle yet bold world.

“There is nothing more to it than the celebration of a giant.”